USB Audio Cables and Sound Quality

With todays use of computers driving DACs even the humble USB cable has now turned into an expensive audio accessory that people spend literally hundreds of £/$/€ on.

There are entire forums full of people who swear blind that these cables impart magic to the sound but when pressed have to admit that they don't have any idea why they work. The manufacturers don't appear to have any idea how they work either.

However these people defend their cables with great vigor and will attack anyone asking simple questions like 'how does it work?' like piranhas after a nice steak.

Physics and Reality meets Hype

The problem with cables and their affect on the 'clarity', the 'smoothness' and 'depth' etc. (add all positive audio buzzwords) is that USB is a block based digital protocol that ends up transmitting serial data from one end to the other. The cable itself is a differentially balanced transmission line with a termination spec of 45 ohms per leg.

There is no way of changing the digital data whatdoever and in digital some bits are worth 6dB, others -96dB or less - so if something did change them in a cable the result would be communications failure.

As long as the cable is reasonably in spec the only possible mechanism for error is small reflections adding jitter, which is not important for the following reasons:

- The block based USB digital stream is by definition breaks up any timing information

-

The thought that a cable's reflection will add or reduce the amount of jitter already in the data from the PC/device is naive

-

Final jitter will depend upon the end DAC that reconstructs the USB data into the data that's clocked into the actual DAC

-

Any cheap DAC that fails to re-time the data in a meaningful way could hardly be marketed as HiFi anyway as timing is fundamental to distortion.

-

The people discussing cables overlook that fact that most of the audio peaks they are listening to are not what they imagined but simply cut off into smooth or noisy flat tops.

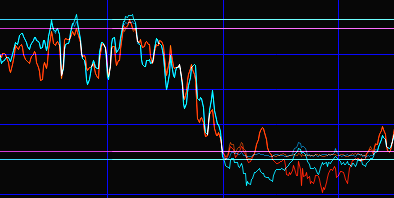

For electrical engineers a simple eye diagram tells us if the USB cable is performing properly, a £200 oscilliscope is all that is required for this simple, yet effective test.

Eye Diagram

Why some USB cables sound different

One universally agreed fact about USB cables is that the digital data coming out of them, at any price, is exactly the same.

The mystique is that somehow cable X for $YYYY is somehow able to impart a luxurious rich sound when others sound thin, veiled or harsh. But logically this is not because the digital data is changed: it isn't. Everyone agrees on that.

So if the data is the same, what's the difference? Well, there are the following real effects:

- The resistance of the shielding

-

The resistance of the ground

-

The resistance of the power (the DAC is very cheap or a very poor design if this affects anything)

-

The coupling of noise into ground or power (minimal as it's a differential signal)

-

RFI rejection (solved by coiling in a few turns of the cable)

The main one of these is the ability of a USB cable - like any cable - to form a ground loop. A very subtle ground issue can cause cables to sound quite different, the cable with the biggest ground and/or shield resistance will sound better.

So ironically a 99p 2M long USB cable will often sound better than any fancy audio one.

How cable sellers damage your sound quality

Spending real money on mystic USB cables is not just a complete waste of money but it has the horrible effects of:

- Splitting the audio community into the tribal lines of those who believe in a mystical branch of physics that a cable stuffer stumbled upon in their living room - and those who know something about physics, electronics and who actually build and design the audio components they rely on.

-

Diverting HiFi revenue down blind alleys away from real devices with real benefits, a costly distraction that is bleeding the life from the real manufacturers.

-

Convincing educated outsiders that HiFi really is a lunatic cult that concentrates on the irrelevant while blithely ignoring the reality on the ground of the constant supply of seriously damaged digital sources and a stagnating device market kept alive by the surround sound industry and snake oil salesmen.

This money for old rope culture is therefore not just a tax on the naive but very damaging to the HiFi industry as it concentrates money into the charlatans at the expense of those genuinely trying to improve the sound with honest hard work. For instance it's common for people to pay £300 for a cable because they want to support the inventor 'exploring new areas of HiFi' while ignoring the honest manufacturers.

Every £100 spent on pointless cables is £100 less available for DAC R&D or better recordings. No wonder music companies treat HiFi with such disdain as they sell their poor distorted, compressed and clipped product on CD to the ignorant masses: the HiFi community is too busy arguing about irrelevant cables, bitrates and the latest mystic sound con-trick to focus on the reality of their situation.

Summary

Cables are not just a serious waste of money, they are a dangerous distraction damaging our industry and therefore the sound we hear.

The issue today is that of the quality of the source, when Linn started up in 1973 they correctly identified the source as the most important part of the chain, which ushered in a huge growth of both HiFi and sound quality. Since then we've forgotten that lesson and not only listen to distorted, clipped and compressed rubbish mixed for a car, but we ignore that and argue about how many hundreds of dollars/pounds/euros it's worth spending on a bit of wire to digitally transport that distorted mess to our precious DACs.

From Sarah Mclachlan's superb Shine On/In Your Shoes CD track, damaged with severe clipping as sold by the record company as 'CD Quality'. Can you find a cable that can fix 6dB of damage to the peaks? Not even eliminating a ground loop with a $10,000 USB cable can do that.

At CuteStudio we found this damage unacceptable so we developed SeeDeClip4, so the music we listen to has far less distortion than when you listen to the very same track, because we still follow the Linn philosophy that the source is important.

Actions you can take

People tend to read articles and then - regardless of their acceptance or dismisssal of the facts - carry on regardless. However there are some very simple things you can do to educate yourself about the music you listen to and allow you to improve the quality of the sound.

Step 1: Examine what you listen to

Not such an issue for classical or jazz music lovers perhaps but any modern popular music today is usually badly damaged, including the favourite tracks you listen to.

So download Audacity, rip a CD to your PC and look at the waveform and zoom into the loud parts. You can then decide if it looks like music or not, and guess at the distortion caused by the clips.

Step 2: Prioritise your spending

After step 1 you'll have some different ideas about what CD Quality means, start investigating 'Mastered For iTunes' masters which are largely unclipped and search out older CD pressings that are ideally pre 1992. Some live DVDs also have good quality sound tracks, forget the coding and bitrate, we're fighting > 50% distortion levels with these clips, selecting a track free of that trumps and other argument.

Step 3: Monitor your sources, consider selection and repair

Regardless of whether you use SeeDeClip4 or pay for the extended declipping features downloading this free program and getting it to scan and grade your music collection for quality will allow you to lookup and see which are your best recordings and which are the worst.

SeeDeClip is an honest piece of software that does it's best to measure and repair mastering damage, it's not a £300 piece of wire it's a 50,000 line piece of expertly crafted software that will reduce clipping and compression distortion in digital music for free or under £20 for the advanced features.

Cash from sales doesn't go into marketing the next house wire stuck into a hosepipe or what passes for audio cables today, but goes straight into R&D to analyse and repair digital music damage to directly reduce distortion to the sound.

|

|

|